#BlackLivesMatter

ABSTRACT

For nearly 400 years, African-Americans have used music to communicate messages with intentions to shed light on hardship, and discriminatory practice, and to help activists inspire and motivate people towards accomplishing social and political change. In this article, I will be creating a limited musical timeline, looking at social and political implications, analyzing and drawing conclusions from a small sampling of music: slave songs, the anthems of the early and late Civil Rights movements, and modern African-American protest music. These songs of protest, activism, and solidarity, which can be interpreted as encoded and embodied forms of collective meaning and memory, express indignation, changed political opinion, attracted people to movements, and respectively promoted solidarity and commitment to abolition, Civil Rights and modern racial justice activism. In addition, with a musician’s perspective, the musical through lines present in three centuries of African-American protest songs will be pointed out and connections made.

Black protest music is more than a culture-current soundtrack for the events surrounding it, and more than just a specific American art form developed and refined by African slaves and their American descendants. Black Americans have used music for nearly 400 years to communicate messages that shed light on hardship and discriminatory practice, to give themselves a voice, and to help racial justice and equality activists inspire and motivate black people and their allies towards accomplishing social and political change. African American protest songs, more than simply artistic expression, can be interpreted as encoded and embodied forms of collective meaning and memory; they express indignation, change political opinion, attract people to movements, they have promoted solidarity and commitment to abolition and Civil Rights and continue to advance modern racial justice activism.

SLAVE SONGS

From the arrival of the first cargo ship of now-enslaved Africans in Jamestown, Virginia in 1619 until 1865, when legalized slavery ended with the Emancipation Proclamation, slave songs gradually evolved to serve a variety of purposes in the African-American slaves’ struggle for freedom: singing as a source of inspiration and motivation, singing as an expression of solidarity and protest, and singing as coded communication. Former slave, abolitionist and author Frederick Douglass describes the songs as “…tones, loud, long and deep, breathing the prayer and complaint of souls boiling over with the bitterest anguish. Every tone was a testimony against slavery, and a prayer to God for deliverance from chains.” (Katz 134) Approaching the meaning behind the plantation songs, we see the enslaved people’s obsession for freedom, abundantly proven by every first-hand document. Slave songs were sung as acts of liberation; for the enslaved African-American people, the very act of being human, of simply wanting to live freely and control one’s own destiny, was a defiant act of protest and revolution. Their artistic expression had an empowering and sustaining effect for the people in bondage.

Slave songs, also called slave spirituals, or plantation songs, were multi-purpose musical communications, spread through oral tradition. Former slave, Booker T. Washington, who aided many enslaved people, stated that: “Slaves must not be seen talking together, and so it came about that their communication was often made by singing, and the words of their familiar hymns, telling of the heavenly journey, and the land of Canaan, while they did not attract the attention of the masters, conveyed to their brethren and sisters in bondage something more than met the ear.” (Bradford 27) Singing was one of the only emotional and spiritual outlets available to slaves; the early plantation songs contained the hopes, dreams, frustrations, and fears of generations of enslaved African-Americans. The composers of most of these plantation songs are not known; they are a genuine folk music. Because the songs were spread through the oral tradition, the lyrics varied by region. The songs seemed to stem from the slaves’ acquired Christian faith, but some might argue that mentions of heaven did not necessarily mean life after death, but rather, might simply be freedom: life away from the plantation, away from slavery, or in the safety of the North, or in Canada.

Singing plantation songs, while at work in the fields, communicated the slaves’ resignation or resistance to forced labor. As Frederick Douglass explained: “Slaves are generally expected to sing as well as to work. A silent slave is not liked by masters or overseers. . . .This may account for the almost constant singing heard in the southern states. . . .I have often been utterly astonished, since I came north, to find persons who could speak of the singing among slaves as evidence of their contentment and happiness. It is impossible to conceive of a greater mistake. Slaves sing most when they are most unhappy. The songs of the slaves represent the sorrows of his life; and he is relieved by them only as an aching heart is relieved by its tears” (Douglas 75-76). Work songs were generally encouraged by the slave owners, who saw them both as means of increasing the slaves’ work output and, ironically, keeping up their morale. Slaves sang songs at work not because they were happy but to try to make themselves feel better and to help themselves and their neighbors keep up the work required of them.

Many plantation songs were thinly veiled expressions of communal protest against slavery and oppression. Slaves, with intention, created double-entendre songs, as a strategy of encouragement while disguising plans for escape and freedom. “Go Down Moses” for example, compares the enslavement of African Americans with enslaved Hebrews in the Bible, drawing its inspiration from the biblical story of Moses, who was commanded by the Lord to lead the Hebrew people out of slavery to the Egyptians.

When Israel was in Egypt land Let My People Go! Oppressed so hard they could not stand Let My People Go!

The famous Underground Railroad conductor, abolitionist Harriet Tubman, was also known as Moses. “Go Down Moses” works on two levels, drawing on the story from Exodus as a source of inspiration as well as supporting the work of the African-American Moses: Harriet Tubman. Some of the songs sung on plantations offered specific strategies and escape routes. “Wade in the Water” reminded runaway slaves how to throw off the scent of tracking bloodhounds. “Follow the Drinking Gourd” provided slaves with a coded map that would lead them to freedom in the North; the refrain told them to keep their eye on “the drinking gourd” (the big dipper) for the stars that traced the edge of its ladle pointed toward Polaris, the North star. (Darden Vol.1, 47) Children were brought up on these songs, and presumably understood their dual-meanings. The slaves of the South hoped and believed that God would intervene and the songs they sang communally helped uphold their faith in deliverance, but after being set free in 1863, the old plantation songs and hymns seemed to be no longer needed.

EARLY CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT SONGS

After Emancipation, as African-Americans adapted to changing times, slave spirituals were re-fashioned into songs of protest and inspiration advancing the early Civil Rights movement. Booker T. Washington, African-American educator, author and advisor to American Presidents wrote about the transition of the slave songs: “Most of the verses of the plantation songs had some references to freedom…True, they had sung those same verses before, but they had been careful to explain that the freedom in these songs referred to the next world…now they gradually threw of the mask, and were not afraid to let it be known that the ‘freedom’ in their songs meant freedom of the body in this world” (Washington 19-20). After Reconstruction, the new freemen found the South to be bitter and harsh. Promises were broken and Jim Crow laws enacted; conditions differed from slavery only slightly, and murders, rapes, and intimidation were prevalent. Freedom, equality and justice were in short supply. While it was feared that the plantation spirituals would be forgotten, they survived, primarily through the organization of African-American churches. Former slaves who did not flee to northern cities turned to the African-American church which became an “extension of family” and provided school, lecture halls and recreational centers; church was a safe place to gather and share information. (Litwack 379) Within the churches, new faith-based freedom songs were taking shape, and the spiritual was born. At the same time, after the 13th Amendment was ratified, African-Americans were allowed to start their own institutions of higher learning and many of these colleges formed choirs, who toured America raising money for their institutions and to present black choral works. The most famous original touring group was the Jubilee Singers from Fiske College in Nashville, which toured along the Underground Railroad path in the United States, and performed in Europe. Of interest is the fact that white men in blackface sang some of these same songs in minstrel shows around the US during this time period. The Jubilee Singers are credited with popularizing the African-American spiritual among white and northern audiences in the late 19th century. Their repertoire was, in itself, protest music, in that they broke racial barriers in the US and abroad, and, through their concerts, raised money to support their school which stood for proving that African-Americans were the intellectual equals of whites. The newer spirituals and the former plantation songs were spread throughout the country. Radio and the new technology of electrical recording also allowed widespread hearing.

One of the earliest, most influential, unifying and sustaining pieces of African-American activist music, originating in the earliest days of the Civil Rights movement, is Lift Ev’ry Voice And Sing. In 1899, James Weldon Johnson, then a high school principal and poet, wrote a poem for a gathering at his school in Jacksonville, Florida; African-American leader Booker T. Washington would be visiting on the occasion of Abraham Lincoln’s birthday. Twenty years had passed since the end of the Reconstruction era, and lynchings were becoming more frequent in the segregated South. Johnson began with a powerful and simple message, and a call to action: Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing. (Mahmic-Kaknjo)

Sing a song full of the faith that the dark past has taught us. Sing a song full of the hope that the present has brought us.

Johnson emphasized the shared conditions and hardships of the African-American people:

Stony the road we trod Bitter the chastening rod Felt in the days when hope unborn had died; Yet with a steady beat Have not our weary feet Come to the place for which ur fathers sighed?

and championed their strength and resolve to persevere:

We have come, treading our path thro’ the blood of the slaughtered Out of the gloomy past Till now we stand at last Where the white gleam of our star has cast.

The song, more of a hymn or anthem than a true spiritual, would serve as a musical protest against the humiliating conditions of Jim Crow and the wave of lynchings and violence sweeping the South. In recounting the bloody past, Johnson’s lyrics advance the idea that it is through the act of standing and singing, that African-Americans most powerfully and persuasively articulate their difficult and dangerous situation, as well as their collective triumphs.

Musically, we see in Lift Ev’ry Voice elements of the slave songs that came before it. James Weldon Johnson’s brother, John Rosamond Johnson, a classically trained musician, set the stanzas of Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing to music. (Mahmic-Kaknjo) Its use of a simple, memorable melody and measure-by-measure block chord accompaniment imitates the reliance on the oral tradition of the spirituals, a through line, and the accompaniment and vocal harmonies also emphasize the meaning of the lyrics. Lift Ev’ry Voice is written in a 6/8 time signature, but its performance follows a 12/8 phrasing like the gospel music growing in popularity and relevance during this same time period. One example of the way the music illuminates the meaning of the text is in the ending line: “sing a song, full of hope that the present has brought us”. To hold the “us” on a fermata (indicating a note that is untimed and held out for as long as the singer or song leader desires) signals the way that African-American people will collectively be held in community together, eternally. The song concludes with a dramatic extended dominant-seventh chord which resolves into a major I; its final notes ringing in harmony and proclaiming victory. (Redmond 73)

Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing, first sung by 500 of Johnson’s students, quickly grew in popularity; it became a rallying cry for black communities, first throughout the South, then the country, and it was widely used as a “collective prayer” (Mahmic-Kaknjo). Black churches embraced it as a hymn; it was sung in school assemblies and performed at graduations. In Maya Angelou’s 1969 autobiography, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, we learn that the song was sung at her eighth grade graduation, a consolation and affirmation after the educational aspirations of her class are belittled by a white school administrator. 20 years later, it was named the official song of the NAACP (Redmond 76). Johnson became employed as an organizer by the NAACP, with the task of growing their membership; while black southerners did not have a relationship with this national organization, the adoption of this piece, which had long been a beloved part of their culture, was a mobilizing feature that drew a great many members. A stanza was used in the benediction at Barack Obama’s inauguration. Often referred to as the Black National Anthem, Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing was most recently performed by Beyonce Knowles in her headlining set at the Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival on April 14th and 21st, 2018. Beyonce, one of America’s biggest musical performers, and the first black woman to headline at Coachella, must have wanted to draw her black fans back to their roots and provide context and encouragement for the continuing struggle. Her performance resonated in particular with black audiences live-streaming from home, and according to social media response, it was, politically and historically, the most significant moment in her set.

39 years after Lift Ev’ry Voice, Billie Holiday’s 1939 song about racist lynchings–Strange Fruit, shocked audiences and redefined popular music. Abel Meeropol wrote Strange Fruit, inspired by a grotesque photograph of the lawless double hanging of Thomas Shipp and Abe Smith in Indiana in 1930 (Darden Vol. 1, 93). Lynching was the most vivid symbol of American racism, representative of all the subtler forms of discrimination. Strange Fruit is considered to be the first true protest song of the African American people and is unique in that its political content is not a barrier to greatness, but rather, its source. A door was thrown open by Meeropol and the incomparable Holiday, and the country looked inside. The first four lines make the terrible truth clear to the listener.

Southern trees bear a strange fruit Blood on the leaves and blood at the root Black body swinging in the Southern breeze Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees.

It is short, slow, and simply orchestrated, which made it possible for less-skilled singers to perform at civil rights events. A great many singers have since attempted it; including Nina Simone and Beyonce, showing that it has a place, generations later, in the body of African-American protest music. Time magazine named Billie Holiday’s first studio version of Strange Fruit, recorded in 1939 the “song of the century.”

Throughout the first forty years of the twentieth century, race relations and the subordination of black southerners remained largely unchanged. In addition to Holiday and others who sang jazz and blues, a few talented classical singers, including Marian Anderson–one of America’s greatest contraltos, kept the protest spirituals in front of white audiences (Darden Vol. 1, 94). Even while the spirituals and early protest music, shared through radio and recordings, made known the hardships of the African-American people, discrimination, racial violence, racial inequality, and segregation persisted, even though World War II, in which more than a million black Americans fought. Some of these early protest songs were used in labor strikes as unions formed. After the war, a more specific struggle began over the meaning of freedom and equality; it would be fought in Montgomery, Selma, Birmingham and Little Rock.

THE SONGS OF THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT

Music does not substitute for political protest, just as gospel music does not replace Christian faith, but the music associated with the struggle for Civil Rights in the 1950’s and 1960’s became a significant form of that protest rather than an adjunct accompaniment. The southern Civil Rights movement involved a great deal of grassroots music-making, and while the movement was aided by professional popular musicians, some of them white, the day to day mobilization required mass song leading and singing as “prelude, accompaniment, and sequel to movement activities” (Rosenthal and Flacks 198). The battle for self-definition for African-Americans was waged in song, long before it was waged in congress. Students and protesters and congregants in each city sang We Shall Overcome, Rock of Ages, Swing Low Sweet Chariot, The Battle Hymn of the Republic, Oh Freedom, and the defiant Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me ‘Round. Freedom Rider Jean Denton Thompson said the songs gave her and her friends the strength to continue on, and the reassurance that they were doing the right thing, while inspiring her and giving her a connectedness with her fellow protesters. (Darden Vol. 2, 642) Dr. King and other leaders used the Christian hymns and anthems especially to underscore and support their non-violent message, to provide hope and endurance. The Civil Rights Movement cannot be separated from its music.

Arguably the most important piece of art to come out of the Civil Rights movement is We Shall Overcome. Though much of America believes that We Shall Overcome was written by white folk singers, it was no folk song, “To African-Americans We Shall Overcome was an anthem of faith and hope–a sacred promise by their creator…sacrosanct” (Gamboa 2). Four folk singers, including Pete Seeger, claimed it was from unknown origin, while historians claim that its precedent– I’ll Overcome– was actually written by Louise Shropshire, a composer of hymns and a close friend of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. (Gamboa 4). There is no doubt that it grew from roots in black spirituals and rose to prominence as the anthem of the Civil Rights movement, but it was first employed in political activism as a strike ballad used in the 1945-1946 tobacco strike in Charleston where black women in the tobacco industry asserted their rights to a fair work environment (Redmond 142-143). David Halberstam, a journalist for the New York Times who covered the mass sit-in in Nashville in 1960, called it “a modern spiritual which seemed to have roots in the ages, the perfect song for this particular moment” (Darden Vol. 2, 548). It was also in Nashville that the long tradition of linking hands and crossing arms right over left while singing We Shall Overcome began. At student sit-ins to desegregate lunch counters throughout the South, its words and its faith reflected the students’ determination and the movement’s purpose (Darden. Vol. 1, 548). We Shall Overcome was brought out at every gathering, every meeting, every protest; the singing sustained students and marchers and Freedom Riders. We Shall Overcome closed all mass meetings throughout the years of the Civil Rights movement. Other movements, at home and internationally, including recent black protest marches, have used the song; its strophic form allows for easy substitutions of different lyrics and languages.

MODERN RACIAL JUSTICE PROTEST SONGS

With the introduction of MTV and VH1, in the early 80’s, music videos became another outlet in which to share African-American protest music and message. Rap and hip hop emerged from the streets and the anger in this next wave of protest music was heard and seen on the tv screen as the artists wished to present it. Public Enemy was known as the first protest hip-hop group; they created a new form of musical expression with which African-Americans could share their experiences and let the world see their truths. One of their notable breakthrough recordings was 1989’s Fight the Power, which incorporated references to African-American culture, and included Civil Rights song samples and sounds of black church services, and which takes a stand against those who abuse their power. In the same vein, NWA’s F*#k Tha Police, which is featured on the Straight Outta Compton record, criticizes the local police force for stereotypical racial profiling and police brutality; its accompanying video depicts a courtroom where attorneys prove how the police department is focused on perpetuating criminal stereotypes of young black men.

There’s a unique connection or through-line between early rap protest music and the songs of slavery and it has to do with freedom of expression. When other forms of expression are controlled or forbidden, art becomes loaded with political significance. Chuck D of Public Enemy explained: “Everything else [in poor urban neighborhoods, in the 80’s] was taken away, so all that attitude…leads into rap as a point of vocal expression for the black man…because black males did not have any way to express themselves” (D 364). Looking back, the prominent role music played in the American slave culture was not simply due to the African traditions; few other forms of expression were permitted on the plantation, so slaves pushed their songs front and center, as a way for people in bondage to collectively find a voice. This confirms a connection between movements, but, in regards to preferred mode of expression, there are differences. Some may argue that rap and hip-hop protest music is not as appropriate for all gatherings or settings as the more melodic spirituals that feature hopeful symbolism rather than explicit imagery and lyrics. But it can also be argued that participatory singing of Civil Rights movement church songs may be more beneficial in serving the committed than in educating or changing the views of people of different backgrounds or generations.

In the modern Civil Rights movement and its music, the question that black people and their allies ask is: who and what should be blamed for injustice to black people in America; one faction believes in self-uplift to break cycles, while the other camp wants to hold white America and its justice system responsible for centuries of violence and injustice. Hip hop and rap emerged, and both embody and advance the protest aesthetic (Gothelf 1). Music from a new generation of freedom fighter’s addresses, with powerful black voices, both sides of the debate, offering guidance for healing from within and telling how to protect against outside forces that devalue black lives. Current racial justice movements–The Equal Justice Initiative, #BlackLivesMatter, rapper Common’s Imagine Justice Initiative, Color of Change, etc.–promote racial and economic equality, seek to reform the judicial system and challenge the deep-rooted racism fostered by a system that to this day uses any means–violence, wrongful convictions, mass incarceration, and even murder.

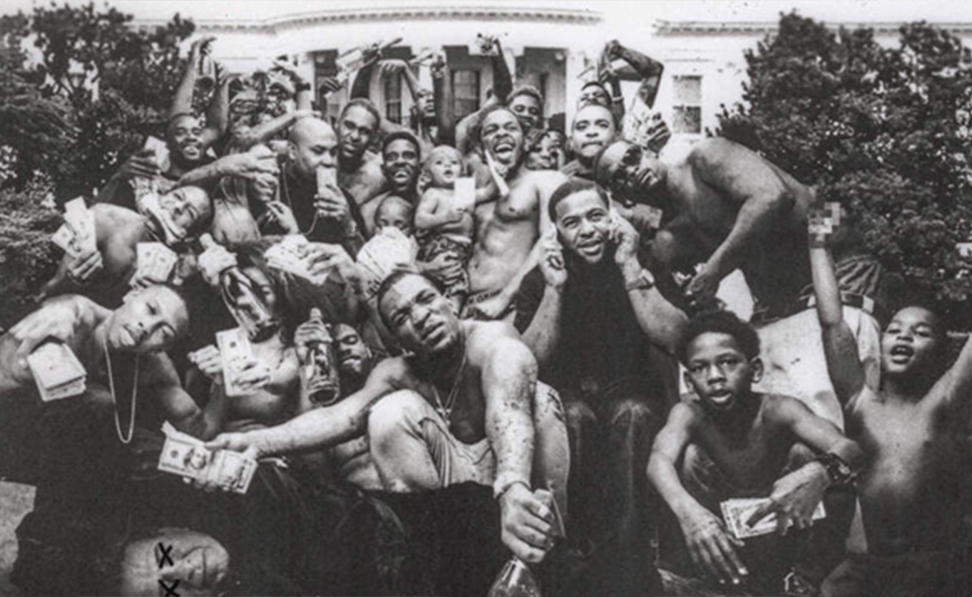

In 2015, African-American rapper and Pulitzer Prize winner Kendrick Lamar released his third album, To Pimp a Butterfly, featuring a song that became associated with the #BlackLivesMatter movement after participants in several youth-lead protests were heard chanting its chorus. Multiple publications named Lamar’s Alright, the ‘unifying soundtrack’ of this movement.

When you know, we been hurt, been down before, n***a When my pride was low, lookin’ at the world like, where do we go, n***a? And we hate Popo, wanna kill us dead in the street for sure, n***a I’m at the preacher’s door My knees gettin’ weak and my gun might blow but we gon’ be alright N***a, we gon’ be alright N***a, we gon’ be alright We gon’ be alright Do you hear me, do you feel me, we gon’ be alright N***a, we gon’ be alright Huh, we gon’ be alright N***a, we gon’ be alright

Do you hear me, do you feel me, we gon’ be alright Alright was written as an affirmation of resilience in the face of fatal police (Popo) shootings; in the last six months of 2014, during the recording of To Pimp a Butterfly, 3 African-American males: 18-year-old Michael Brown, living in Ferguson, Pennsylvania, 43-year-old Eric Garner living in Staten Island, New York, and 12-year-old Tamir Rice living in Cleveland, Ohio were murdered by police in their hometowns. While it is raw and explicit, Alright’s reliance on faith while in dark times, and its call and response chorus are reminiscent of both the plantation songs and the Civil Rights anthems. In four-time Grammy-nominated protest song Alright, and in other songs on To Pimp A Butterfly, Kendrick Lamar paints a graphic picture of the modern black experience in America, and in particular highlights gun violence and police shootings, while also acknowledging the 400 years of struggle that led up to this point. Alright is an activist anthem promoting positivity beneath a cloud of civil unrest. From a different musical genre but the same generation as Lamar, an R&B artist has been using her platform to share an activist message: Grammy nominated Andra Day has impressed with two songs in particular. Stand Up for Something, which features Common, urges armchair activists, presumably of all races, to “stand up for something” and “walk the walk”. It, like the slave songs, the spirituals and the Civil Rights songs, draws on Christian symbolism and preaches respect and love. Rise Up, an anthem off her platinum album Cheers to The Fall, hearkens back to her church roots, and speaks to the weariness of the struggle and the importance of persevering in order to “move mountains.”

You’re broken down and tired Of living life on a merry-go-round And you can’t find the fighter But I see it in you so we gonna walk it out Move mountains We gonna walk it out And move mountains And I’ll rise up I’ll rise like the day I’ll rise up I’ll rise unafraid I’ll rise up And I’ll do it a thousand times again And I’ll rise up High like the waves I’ll rise up In spite of the ache I’ll rise up And I’ll do it a thousand times again For you

Day has performed Rise Up at protest marches including March for Our Lives in Washington, at the Democratic Convention, at The White House and again performed the song for the live television special, Shining a Light: A Concert for Progress on Race in America, amongst other tv programming. The lyrics of Rise Up have been printed on 50,000 McDonald’s beverage cups. She was named the Outstanding Artist of the Year by the NAACP. Day has been quoted as saying that she ties her music to activism because she wants to tell the truth about the racial terror that has happened and that is still happening today in this country. Her music and her message has been well-received with several demographics, perhaps because she is a powerhouse singer, and perhaps because her message is inspirational but not graphic in its description of the “racial terror”. Day’s message and delivery may remind the public of the African-American protest music that is her inheritance and serve to inspire the new generation of marchers and influencers.

THROUGH LINES

There are through lines to be found in 400 years of African-American protest songs–channels of communication for activists within movements, but also between different movements, and between movement generations. Music enters into what psychologists call the collective memory, and songs can conjure up long-lost movements from extinction, as well as reawaken forgotten structures of feeling (Rosenthal and Flacks 160). Through lines include expressions of Christian faith, repetitive choruses and antiphonal responses (call and response), simple singable melodies, freedom symbolism, and the use of musical expression as an outlet when no other outlet exists. This body of music allowed protest movements to connect with audiences beyond organizers’ immediate reach. Sometimes a protest song or anthem actually exceeded the reach of its movement; these songs were products of the movement’s momentum as well as driving forces within them. While the anonymous composers of the plantation songs are long gone, and those who composed the late Civil Rights era freedom songs sung at lunch counters, on bus rides, at sit-ins and in jail, at Little Rock and Montgomery and Selma, are in their eighties or nineties, their songs of protest, faithfulness and solidarity rang out from rallies and marches in Ferguson and Staten Island and Cleveland; these songs have deep roots and radical implications, especially when performed alongside the R&B, hip hop and rap that currently expands the African-American protest canon.

CONCLUSION

The art of the African American people has been and continues to be used to impact socio-political ills. Through musical expression: slave songs, spirituals, anthems, Civil Rights songs, rap and hip-hop protest music, black men and women communicate their pain, alienation, hopes and aspirations, triumphs and expectations, using the wide reach of protest songs to confront their situations and then overcome and transcend them. African-American protest music, from slave songs to #BlackLivesMatter rap, is not merely “art for art’s sake” for, as W.E.B. DuBois declared, “…in the final analysis all art is propaganda” (DuBois 25). 400 years of African American protest music cannot be underestimated in its power to raise the spirits of the oppressed, assist in changing the hearts of their oppressors, and aid in turning around an oppressive system. These songs are absolutely central to the political and societal progress unfolding; the music contains and communicates the beliefs of the performers, who were and still are imaging and enacting change.

WORKS CITED

Bradford, Sara Hopkins. Harriet, The Moses of Her People George Lockwood, 1886.

D, Chuck. “Chucky D Lecture at The University of Pennsylvania.” Nation Conscious Rap. University of Pennsylvania Press. 1991.

Darden, Robert. Nothing but Love in God’s Water. Volume. 1 Pennsylvania State University Press, 2016.

Darden, Robert. Nothing but Love in God’s Water. Volume. 2 Pennsylvania State University Press, 2016.

Douglass, Frederick. “Chapter 6: Treatment of Slaves on Lloyd’s Plantation.” My Bondage and My Freedom. Lit2Go Edition. 1855. Web. April 28, 2018.

DuBois, W.E.B. The Crisis, Vol. 32, October 1926

Gothelf, Jasmine (2015) Check The Rhime!: Hip Hop as a continuation of the African American protest tradition, from David Walker’s Appeal (1829) to Kendrick Lamar’s “The Blacker the Berry”(2015). MRes thesis, University of Nottingham.

“Harriet Tubman (Moses).” | EHISTORY, ehistory.osu.edu/biographies/harriet-tubman-moses. April 10th, 2018 (Date Accessed)

Katz, Bernard. The Social Implications of Early Negro Music in the United States: with over 150 of the Songs, Many of Them with Their Music. Ayer Co., 2000.

Litwack, Leon. Trouble In Mind: Black Southerners In The Age Of Jim Crow. Random House 1998.

Mahmic-Kaknjo, Mersiha. “Http://Cejpaediatrics.com/Index.php/Pt/Article/View/282/Pdf.” The Central European Journal of Paediatrics, vol. 13, no. 1, 2017, pp. 42–45.

Redmond, Shana L.. Anthem: Social Movements and the Sound of Solidarity in the African Diaspora. New York University Press, 2014

Rosenthal, Rob and Flacks, Richard. Playing For Change: Music and Musicians In The Service Of Social Movements. Wesleyan University Press-Routledge, 2011.

Washington, Booker T. Up From Slavery. Doubleday, 1901.

Your doctor may need to adjust your medications to minimize this risk priligy buy 6 Loracarbef success rate 19 less than control S